Orff Schulwerk: Where Did it Come From?

By Esther Gray

Sometimes Orff teachers or students area asked “What is Orff?” or “What does Orff stand for?” Those questions can be hard to answer, because Orff is many different things.

Kids in an Orff class often sing and do movement. In some classes they do plays, puppet shows or music games. They may be in a school which has drums and xylophones, metallophones, recorders, and glockenspiels for them to play.

The special thing about all Orff activities is that they give kids a chance to make up some of their own music and dances, or change and add to music they like.

Orff is the name of a very special man who loved music and loved children. He was one of the first teachers to combine singing and speaking, clapping, dancing and instrument playing for children. Later when other teachers decided to take some of Orff’s ideas and use them with their students, they said they were teaching “Orff.”

Actually what we call “Orff” was started long ago by several different people.

CARL ORFF

One of those people of course was Carl Orff. He was born in Germany in 1895, and he died there in 1982. When he was born in Munich, the city was still governed b a king. Very few people had cars, because cars at the time were still experimental. Many people walked where they needed to go. If they had enough money, they might have horses to ride or to pull their carriages.

People did not have furnaces in their houses. They had to carry in fuel and light it in their fireplaces or in wood or coal-burning stoves. They had no automatic washers and dryers or dishwashers, so they had to wash their clothes and dishes the way American pioneers had to.

Movies, televisions sets, stereos and tape recorders were not in use yet. People who knew good songs or told good stories shared them with others. Musicmaking, storytelling and dancing were important entertainment for everyone.

Babies were born at home in those days. Baby Carl was born in a big three-story house at the edge of Munich. It had a nice front yard with tall horse chestnut trees in it and a big back yard full of trees and wildflowers. His mother had a special flower garden and he loved to play there.

His father was an army officer. They lived near his father’s base. The practice field for the army band was across from the Orffs’ house, and it was fun to listen to the music.

Carl’s mother played piano. They say that even when he was little, Carl liked all kinds of music. When he was old enough to crawl, he liked to sit under the piano beside his mother’s feet and list to her play. He would pound on the floor to the beat of the music.

When he was old enough, Carl begged his mother to let him play on the keys with her. She would sometimes take his high chair over to the piano and let him sit beside her and “play” along.

Finally when he was five, his mother began to give him regular music lessons. His little fingers got tired practicing exercises, but he was excited to learn how to read and write down music. Paper was quite valuable at that time, so children learned to write on slates which could be erased and used over and over again.

Carl’s mother wrote five lines for a staff and then together the two of them wrote down a lullaby he had made up. His mother added some notes for a simple accompaniment, and there was his first composition!

When he was nine years old, he started writing stories and poems. He began a special project of collecting all the information he could find about plants which had been used at some time for medicine or magic. He studied science books and fairy tales for this hobby.

Carl had a little sister, Mia, who was three years younger than he was. The two got along quite well. They would play four-handed piano music together. When young Carl wrote little songs, Mia would perform them for the family.

From the time he was three, his family spent summers in the country at a farmhouse they rented near a large lake, the Ammersee. There were farm fields, wildflowers and cattle near the lake, and the beautiful Alps mountains in the distance to look at. Carl Orff always loved the beauty of the country.

When Orff was 16 he discovered the music written by a French composer named Claude Debussy. Orff was so interested in the sounds Debussy used in his music that he went to a lot of trouble to find copies of his favorite pieces. He was excited studying the music, figuring out why it had such a special sound.

Debussy had heard unfamiliar music from China, India and Java at a special world’s fair in Paris in 1889, before Orff was born. At the fair there were huge powerful gongs and elegant dragon-shaped instruments like metallophones which were decorated with gold. Debussy went day after day to hear the colorful orchestras. He borrowed musical ideas from the exciting things he heard.

Carl Orff was so interested in this that he went to a museum in Munich and studied all the instruments they had from the Far East. He got close to a large gong and quietly played it. Much later he recalled how thrilled he was with the sound. He felt like there was a whole exciting world of music in those instruments which nobody in Germany was using at that time.

During the next few years many important things happened in Carl Orff’s life. He got his first job which was in a theater making music for shows, and he loved the work. He was drafted as a soldier in World War I, and he was sent home wounded. After he got well, he married and had a little daughter.

Times were changing. The first cars, radios and telephones were being used by rich people who could buy them. There were streetcars in Munich. However it was a difficult time called Inflation, and German money for some complicated reasons was becoming less and less valuable. Food and clothing suddenly cost much more than they ever had before. Poor people had trouble buying enough food. People who had money sometimes had to take a basket or wheelbarrow full of money to the store in order to have enough to pay for what they bought!

DOROTHEE GÜNTHER AND THE GÜNTHERSCHOOL

In 1923 Carl Orff met a talented woman named Dorothee Günther who worked with him at the theater and then started the school where “Orff” activities were first taught.

Dorothee Günther had studied art and gymnastics, and she believed that most students did not get enough chances to do art and music and movement activities. She was convinced that such experiences were important for young people. She decided to open a school where these things would be taught for teenagers and young adults who wanted to become teachers, dancers and musicians.

In 1924 when the Günther School was opened, few women had the opportunity to start schools. Günther was able to because she had worked hard studying gymnastics and physical education. Then by teaching her first class she figured out exactly what kinds of studies she thought would be important in a new school. People were impressed with her ideas, and they helped her get started.

Because Günther had gotten to know Orff’s work, she invited him to work with her at the Günther School. She knew he would be a fine musician and a good teacher. Five years later the school had many students. It had a popular dance group that performed in Germany and in other countries.

GUNILD KEETMAN

One of the students who came to the school, Gunild Keetman, did such good work that when she graduated she was asked to become a teacher at the Günther School. Nobody knew at that time she would end up spending her life teaching and working on Orff activities, and that with Carl Orff she would write the Orff-Schulwerk books which music teachers use today.

Gunild Keetman was a child around the same time when Carl Orff was. It was a time when little girls were expected to always wear dresses and to work at being polite and lady-like. Little Gunild grew up in a family where music was so important that she was given both piano lessons and cello lessons.

She loved music, but her teachers emphasized practice exercises, printed music and sitting quietly. They never encouraged her to make up pieces. It was not o.k. to change the things she played. Of course practicing music is important, but it is not the only thing students can do. Those teachers did not realize how much fun it can be for kids to invent tunes of their own or dance while they are learning music.

Gunild Keetman never stopped being interested in music and art and dancing. When she grew up she decided to study about music and art history and physical education. She believed that these things were all important for children.

Keetman was excited when she heard that at the Günther School students worked hard to learn music and dance, and that all students there learned both music-making and dancing.

When she came to the new school, she was surprised to find that her new teachers did not simply teach her some songs and dances. Orff and Günther expected all the students at their school to make up music and dances! They gave many lessons that helped students learn difference ways to make music. But they did not teach students to copy what had been done before. They taught them to always use what they were learning in order to make interesting new music.

Gunild Keetman recalled many years later how students would sit for hours at the piano, trying out new things. Of course many things they played were not successful. That is the way it is supposed to be when people are creating something new. If the students in vented something that they felt good about, they would write it down so they could play it later for Orff.

Sometimes they would take a piece they had made up on piano and play it on xylophones, metallophones or glockenspiels. Then often they were assigned to improvise movement that fit their music. Sometimes it was hard to do, sometimes easy.

They found that they got better and better at inventing music and movement. They got better also at working together. It was easier and easier to think of something new to try when they did not like part of an improvisation.

Some days students took off their shoes and socks and started out creating movement while others improvised music on recorders or barred instruments that seemed to fit the movement they were watching.

Always the students would take turns playing music and doing movement. At times the dancers themselves made music, wearing jingles or rattles on their legs or playing drums or cymbals as they moved.

When a group was able to do that well, they would try to create several parts at once!

Gunild Keetman discovered that it was an exciting way to learn. She was happy she had come to the Günther School.

After she finished her studies there, she was thrilled to be asked to stay and teach the new students. She had been an important member of the school’s dance group, and now she learned to be a good teacher.

THE INSTRUMENTS

When the Günther School opened, Orff did not have the kinds of “Orff” instruments we enjoy today. He began teaching music classes with a piano.

A friend, Oskar Lang, loved exploring second-hand stores and sales. Bit by bit he brought Orff a fine collection that included unusual rattles, little bells and even a large African slit drum.

A year after the school opened, small drums like Orff timpani were invented. Friends gave the Gunther School wood-blocks, bamboo scraping instruments and many different kinds of drums and gongs.

There was something missing. Orff liked the work the students did on these instruments. But he wanted instruments besides the piano that could play melodies.

In 1926, two years after the school opened, he got some help from two women from Sweden who traveled a great deal. They had heard of his music, and they hoped he might bring some Günther School students to perform music for puppet shows they were working on. Orff liked their shows and he thought it might be a good idea. When they heard he liked xylophones, they said they would try to get him one. He did not think they could.

He went on working at the Günther School, and sometime later a large package was brought to the door. Inside was a large African xylophone, a marimba.

Keetman and Orff, Maja Lex (an outstanding dancer) and several Günther School students worked with the xylophone and loved it. They invented a lot of music and exciting dances.

Orff wanted to have more xylophones, but he could not find a way to get them. He was told it would be impossible to build them with German materials, and too difficult to get African materials.

Because he learned that recorders had been used in early times to play melodies with simple instruments, he decided to order some for the school. At that time recorders were rare and few people knew how to play them.

While everyone waited for the recorders to arrive, a wooden box from Hamburg was brought one day to the school. It was from a Günther School student, and in it was a simple xylophone from Africa with 10 short bars.

Orff became excited when he discovered that this instrument was built from a wooden German box that had been used to ship 10,000 nails from Africa! What a surprise! The only African part of that xylophone was the bars.

Orff and Keetman and their friends set a trap. They prepared a special show for a special friend, Karl Maendler, who built instruments. First they played the large marimba and Maja Lex danced The Dance of the Marimba Bars (Stäbetanz). Then Keetman brought out the smaller Nail-box xylophone and played on it. They all hoped Maendler would be fascinated. He was. He watched The Dance of the Marimba Bars three times!

Maendler figured out that they were going to ask him to try to build a xylophone. Normally he built harpsichords! He was intrigued, and he decided to try to build a German xylophone. He finished one, named it an “alto” xylophone and brought it one night to the Günther School. He had tuned it to the D scale because the recorders Orff had ordered would be tuned in D. The students were thrilled. They improvised all evening to celebrate. They begged Maendler to build another and he promised to build a higher “soprano” instrument, which he did.

Finally the recorders arrived. Unfortunately no one knew how to play them. They had no recorder book and no instructions. What a disappointment after all their waiting!

Keetman decided to do something about it. She said, “Give me a recorder and I will find out how it works – in a month the lessons will begin.” She figured it out, and besides teaching recorder lessons, she created recorder books.

THE END OF THE GÜNTHER SCHOOL

Another war, World War II came to Germany at one of the most painful times in human history. Many Germans had hoped that a strong leader, Adolf Hitler, could keep promises he made and help Germany get past the hunger and poverty they suffered. Then everyone would be better off.

Part of Hitler’s plan was to get rid of any people who disagreed with him so he could run the country freely. Another part of his plan was to find somebody to blame for Germany’s hard times. The hard times had not been caused by any particular person or group. Still, some Germans were so angry about working hard and being poor and hungry that they wanted to think it was somebody else’s fault. They were willing to listen to the things Hitler said.

Nobody wanted to believe it was happening, but gradually they found that many good people including teachers, doctors and scientists were being put into ugly, crowded prisons simply because they were Jews or because they disagreed with Hitler’s government. Even children could be arrested by the secret police.

People in Germany lived in worry and fear. Eventually any person with new or unusual ideas could be expected to be punished. Artists and authors had to decide whether or not to hide their beliefs.

The people in Hitler’s government did not like the Günther School. Five years after the war began, they told the Günther School teachers that they could no longer have a school. The police confiscated the school and all its content. Teachers and students were shocked. They believed with reason that they must leave the city or be called into war service.

The year after the school was closed, the school building was bombed during fighting. Most of the special instruments, music and costumes were completely burned up. It was the end of the Günther School which had trained 650 teachers and many dancers. But it was not the end of Orff.

After the war, life was still very hard in Germany. Hitler’s government was ended, but houses, stores and schools were damaged in the fighting, and people did not have enough new material to rebuild them right away. There was not enough cloth and wood to make new clothing and furniture. People did not have enough soap or food.

Dorothee Günther decided to move away from Germany to Italy. Carl Orff began to write an opera.

A NEW BEGINNING

There were still people who remembered the music of the Günther School and liked it. Three years after the war they came to Orff and Asked if he could make up some music like the “Günther School music” to play on the radio for school children. Orff talked about it with Keetman. They wondered if they could. They had only worked with older students at the Günther School, but they believed in the things that had made their work there important to them. They wanted more people to know about it.

Orff and Keetman did write music for the radio programs. In fact, they wrote five books of music in five years (1950-1954) – music for children to perform or work with. After kids heard the music on the radios in their schools, they and their teachers and parents got very excited about the way it sounded. They decided they wanted to try to get Orff instruments for their schools. New ways were discovered to build Orff instruments because the old building materials were not easy to find.

It was the beginning for Orff teachers like the ones today who take Orff ideas and work with them in their own special ways with the children in their classes. It was the beginning for kids around the world who love to make Orff music.

In 1961, about 10 years later, a new school for Orff teachers and students was built. Orff and Keetman had been directing Orff-Schulwerk classes in rooms loaned by another school. When the bulldozers dug a hole where the new school would be built, Orff went to the building site and stood in the dirt looking over the job. He worried a little about whether or not there would be enough students for a grand new building. He need not have worried.

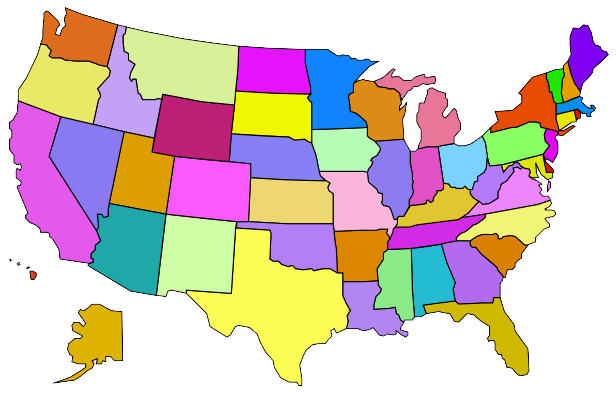

Teachers come from many countries to Salzburg, Austria to study at the Orff Institute. Orff classes are also taught in other countries so teachers do not have to travel far away to learn how to teach Orff.

We cannot name all the places besides the U.S. where there are Orff teachers, but we can list some of them. You might like to find these places on a map or globe: Australia, Austria, Namibia (S.W. Africa), Japan, Brazil, Uruguay, Greece, Mexico, Italy, Malaysia, England, Czechoslovakia, British Virgin Islands, Hungary, Poland, Israel, Sweden, the Soviet Union, Belgium, Canada, and Germany.

In those countries we find what is most important in Orff. Not the books in many languages. Not the instruments. But the people who enjoy Orff.

Bibliography

Günther, Dorothee. :Der Tanz als Bewegungsphänomen,” Rohwolts Duetsche Enzyklopädie, Nr. 1951/52, Hamburg: Rohwohlt, 1962.

Keetman, Gunild. Reminiscences of the Güntherschule. American Orff-Schulwerk Association Supplement Number 13, spring 1978

Gersdorf, Lilo. In memoriam Carl Orff (1895-1982). Orff-Schulwerk Informationen Nr. 29, May 1982. Translated and reprinted, American Orff-Schulwerk Association, October 1982.

Gersdorf, Lilo. Carl Orff: in Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten. Reinbek bie Hamburg: Rohwohlt, 1981.

Orff, Carl. The Schulwerk. (Volum III of Orff’s Autobiography, documentation, an 8-volume work.) Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1976. English Version, New York: Schott Music, 1978.

Thomas, Werner and Williband Götze. Orff institute Year-books. Mainz: B. Schott’s Söhne, 1962 and 1963.